If anyone has any examples of the lace or any equipment or documentation relating to it, I would be delighted to see them.

59 East Street, Coggeshall CO6 1SJ

01376 564443

sara.impey@gmail.com

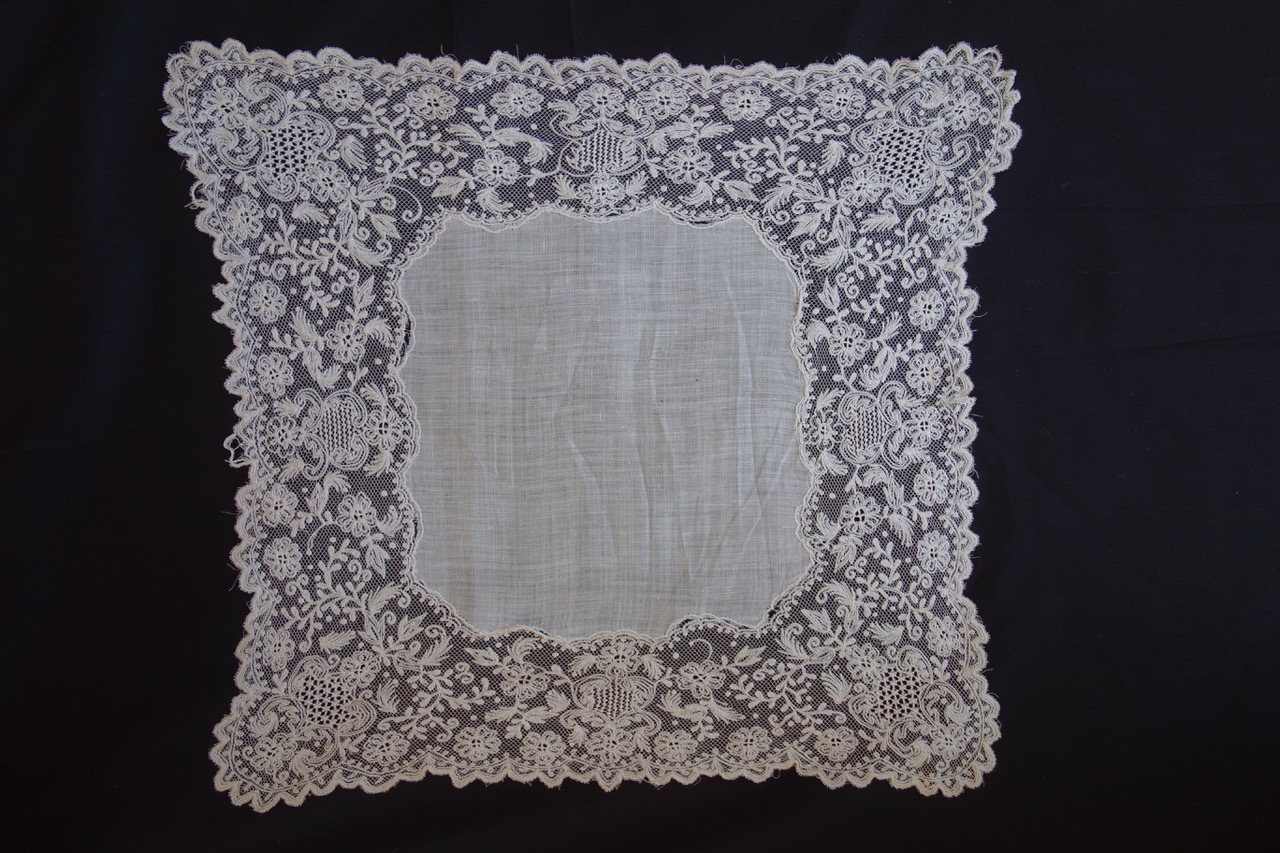

Coggeshall Tambour Lace

Sara Impey

I’m currently researching into Coggeshall lace for a book on the subject, but have yet to find a publisher. Most of the lace-makers lived in Coggeshall, but several came from the surrounding villages, including Earls Colne. Below is a brief history of the lace based on recent findings.

When was Coggeshall lace made? From about 1820 until just after the Second World War. At its peak in the 1850s the industry employed around 450 women and children in the area and supplied a fashionable London clientele. A gown was made for Queen Adelaide in the early 1830s and examples were exhibited at the Great Exhibition in 1851.

What is Coggeshall lace? It’s a type of embroidery on to machine-made net. It’s known as tambour lace because the net is stretched over a frame which originally resembled a tambour drum. The net is embroidered by hand with a tiny hook like a crochet hook, producing a very fine chain stitch which creates the patterns and motifs. Tambour lace was cheaper and quicker to produce than the two main types of lace – bobbin lace and needle lace – but it was fashionable, decorative and and economically significant in its day. It demands a high level of skill from the maker. Women who learnt as children could work fast and efficiently enough to supply the commercial fashion trade.

Was tambour lace made in other places? Yes, it was made in Nottingham, parts of London and Scotland, Limerick in Ireland and also Lier in Belgium and Lunéville in France. The Coggeshall industry was small by comparison but important to the local economy.

How did the industry come to Coggeshall? The tambouring technique is believed to have been introduced in the 1820s by a French or Belgian emigré named Drago and popularised by a Coggeshall silk weaver called Thomas Johnson and his daughters who lived on Grange Hill.

Who made the lace? The makers, known as ‘tambour workers’, were village women and children. Most girls started aged 8. The usual working day for a child in the 1840s was 11½ hours. They were poorly paid, but if all the women in the household made lace they could double the income of, for example, an agricultural labourer in an age in which every penny counted. Women in Earls Colne worked at home, but in Coggeshall many worked in ‘tambour rooms’ which were large workspaces, sometimes purpose-built, with tall windows to let in plenty of light.

How was the industry organised? The women were employed by ‘tambour manufacturers’ – local Coggeshall men who acted as middlemen. They paid the women, provided the materials, supervised the designs and supplied the finished lace to wholesalers in London who advised on fashions – it was vital to keep up with changing trends. Over the nineteenth century about 20 lace manufacturing concerns were recorded in Coggeshall, but many of these were small and came and went in a few years and the trade was dominated by five or six families and individuals who were more firmly established. The largest was James Spurge, who was born in Earls Colne, and employed 100 women from his premises in Stoneham Street. Many of the manufacturers continued their previous occupations as well as dealing in lace. Wives and daughters were often the driving force behind the businesses, both in initiating the involvement with the lace and in the day-to-day management.

How many makers came from the Colnes? In 1861, when the industry was around its peak, there were 36 lace-makers in Earls Colne. Most of them lived in the roads nearest to Coggeshall, such as Coggeshall Road, Tey Road, America Road and Curds Road, though a handful lived in the High Street. This shows how locally concentrated the industry was – there were fewer makers living towards Halstead and Colne Engaine, for example. In one family called Webb from Curds Road the mother and three daughters aged 18, 14 and 12 all made lace. There were also 11 makers in White Colne. The numbers then slowly decreased, as they did in Coggeshall. In 1871 there were 22 makers in Earls Colne, in 1881 there were just three and only one left in 1891. By the turn of the twentieth century there were hardly any makers left in any of the villages, and none in Earls Colne, though there were several remaining in Coggeshall itself.

Why did the industry decline? Changes in fashion, foreign competition and the arrival of machines that could produce a chain stitch all contributed to the decline of Coggeshall lace.

What happened in the 20th century? From the early 1900s the remaining lacemakers were supported by a series of philanthropic local women. Instead of supplying the fashion trade, the lace gradually became a heritage product. One-off pieces were made for bridal wear or as gifts for special occasions. The 1920s and 1930s were successful and items were made for the royal family and national and international exhibitions, but after the Second World War there were hardly any workers left and commercial lace-making in Coggeshall petered out.

Is Coggeshall lace still being made? A revival took place in the 1970s when women came together to learn the skills for their own pleasure. Today there is no-one still making the lace in any collective sense, but there are numerous YouTube videos on the tambouring technique for anyone who wants to learn.